Béla Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta was composed in the summer of 1936, and is widely regarded as a masterpiece of his mature period. Less well known, however, is a similarity between its opening fugue and the first movement of Arnold Bax’s third symphony, composed in 1928-9.

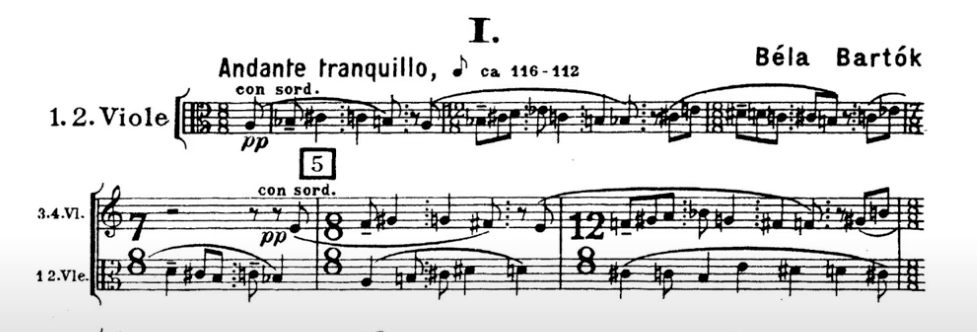

The similarity is easy to spot by ear. Bartók’s fugue begins with a subject whose opening phrase outlines a distinctive shape of A, B flat, C sharp. Bax’s symphony begins with a winding bassoon theme on the exact same pitches. While the Bax is less strictly fugal, the clarinet and flute do join in with imitative entries, and both movements go on to make obsessive use of the three-note shape.

A few commentators on internet forums have noticed this connection, but otherwise I can find no writing on it. So I decided to investigate the obvious question: could Bax’s symphony have influenced Bartók’s MSPC?

I say ‘influenced’, because there is no question of plagiarism here. Despite the striking similarity at their starting points, these two works go in very different directions, each distinctive to their composers. But the possibility remains that the Bax might have planted a seed in Bartók’s mind – a conscious or unconscious seed – that later grew into the MSPC fugue.

For the last few days I’ve been looking at newspaper archives, and every relevant biography in London’s libraries. It seems almost certain that Bartók knew about this symphony’s existence, at the very least. The question of influence is therefore a legitimate one, even if it is impossible to answer definitively.

Bax and Bartók were almost exact contemporaries, born two years apart. And as his statue in South Kensington attests, the great Hungarian made many trips to London to give concerts. He also went to Liverpool, Glasgow and Birmingham. Several of these British engagements occurred in the crucial years between these two works appearing, 1930-6.

At some point it seems Bartók was studying Bax piano pieces with a view to performing them. This was relayed to me some years ago by the Bax scholar Graham Parlett. He has sadly since passed away, and I’ve been unable to track down the newspaper source of this. Nonetheless, more anecdotal information comes from the memoir of Harriet Cohen, Bax’s long-term lover and musical collaborator, to whom Bartók later dedicated part of his Mikrokosmos. She wrote that Bartók ‘much admired’ Bax’s 1922 piano quartet.

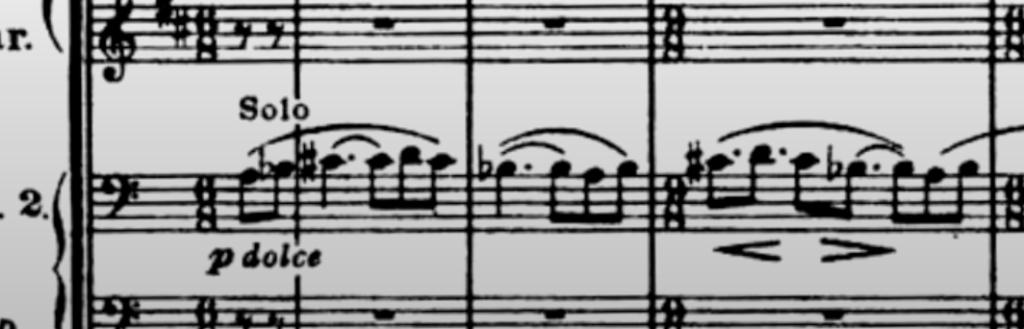

So Bartók had at least a passing interest in Bax’s work. What’s more, the thematic similarity between the two movements is bolstered in a later passage of the Bax, in which he repeats the introduction in the strings. The violas start things off, just as they do in MSPC – in the Naxos/Lloyd-Jones recording, it comes at 12:53. Now look at what happens next…

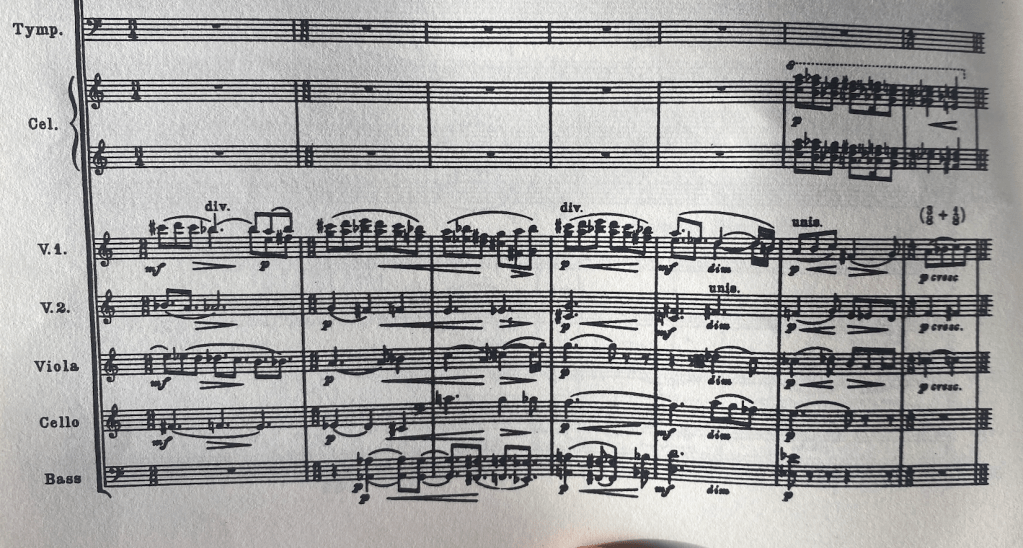

…that’s right, the celesta joins in (and continues over the page). If anything could have influenced MSPC, it’s surely these bars. The celesta makes another prominent contribution when the symphony’s opening theme returns in the third movement’s ‘epilogue’.

How likely is it, then, that Bartók knew this work? Admittedly, I haven’t been able to find a performance of the symphony that coincided with his UK visits. But he almost certainly heard about it through his engagements with Henry Wood, the symphony’s dedicatee who tirelessly championed it throughout the 30s. After giving its premiere in March 1930 to significant press interest, Wood conducted the symphony in every Proms season from 1930-4 (imagine such support for a large-scale new work today!), and took it to Zurich, Rome, and Los Angeles. ‘We are very proud of him’, he later wrote of Bax, adding that the third was ‘perhaps my favourite’ of his scores.

Beecham and Barbirolli conducted performances of it in these years too. Most tantalisingly, several newspapers reported that Adrian Boult was going to include it alongside Bartók’s Four Orchestral Pieces at a BBCSO concert in Budapest in April 1936. What a perfect smoking gun for influence that would have been! But in the end it seems they performed Tintagel instead.

Others may have drawn Bartók’s attention to the work. Harriet Cohen fondly recalled long conversations with him in Strasbourg in 1933, where she was to perform Vaughan Williams’s piano concerto, from which the composer had recently decided to cut a quotation of the symphony’s epilogue. The following year, Bartók’s friend Joseph Szigeti performed the Mendelssohn violin concerto in the same Prom that the symphony featured in.

Arguably, we could go far as to say that, given Bartók’s British connections at the time when this symphony’s fortunes were riding high, it’s possible he felt this was a piece he ought to know. The score was published in 1931, so he could well have got his hands on a copy. And while the first recording was not made until 1944, he might have heard a radio broadcast.

But of course, this is all speculative. Influence cannot be proven, and in one sense, it doesn’t matter, since there’s no real question of plagiarism, and the similarities may be coincidental. But as someone who adores Bax’s beguilingly beautiful but long-neglected symphony, it is disappointing to see that not one of the Bartók books I’ve been able to get my hands on make a single mention of Bax at all – not even Malcolm Gillies’s Bartók in Britain.

Digging into this question has convinced me that Bartók scholars should at least recognise the possibility of influence here. After all, the past does not respect our modern prejudices: Britain may have long since abandoned concert performances of Bax’s symphonies, but the third was considered an important new work in the 1930s. It got an enviable amount of attention, so much so that in 1932 William Walton could hope that his own symphony would ‘knock Bax off the map’. If Bartók encountered Bax’s symphony in any form during his visits here, he would have approached it with that understanding too.

My blog posts are powered by caffeine. You can support Corymbus by buying me a coffee on PayPal, or subscribing to my Patreon.