By Peter Davison

At a time when classical music is losing its cultural significance, it is reassuring to read a book in high praise of major works by major composers, reminding us of a time when serious music was relevant to more than just an educated elite. The American musicologist and critic Jeremy Eichler’s recent publication, Time’s Echo, makes a convincing case that the wide appreciation of great music prevents collective amnesia, thus lessening the chance that humanity will repeat its most egregious errors. In our contemporary world, the re-emergence of authoritarianism and bitter ideological disputes feels like a regression to a former historical era. We can even perceive the slow decline of classical music as evidence of a more general wish to forget who we are, as political expediency and the banalities of celebrity culture obscure historical truth. A society that prefers fantasy over reality is surely in trouble.

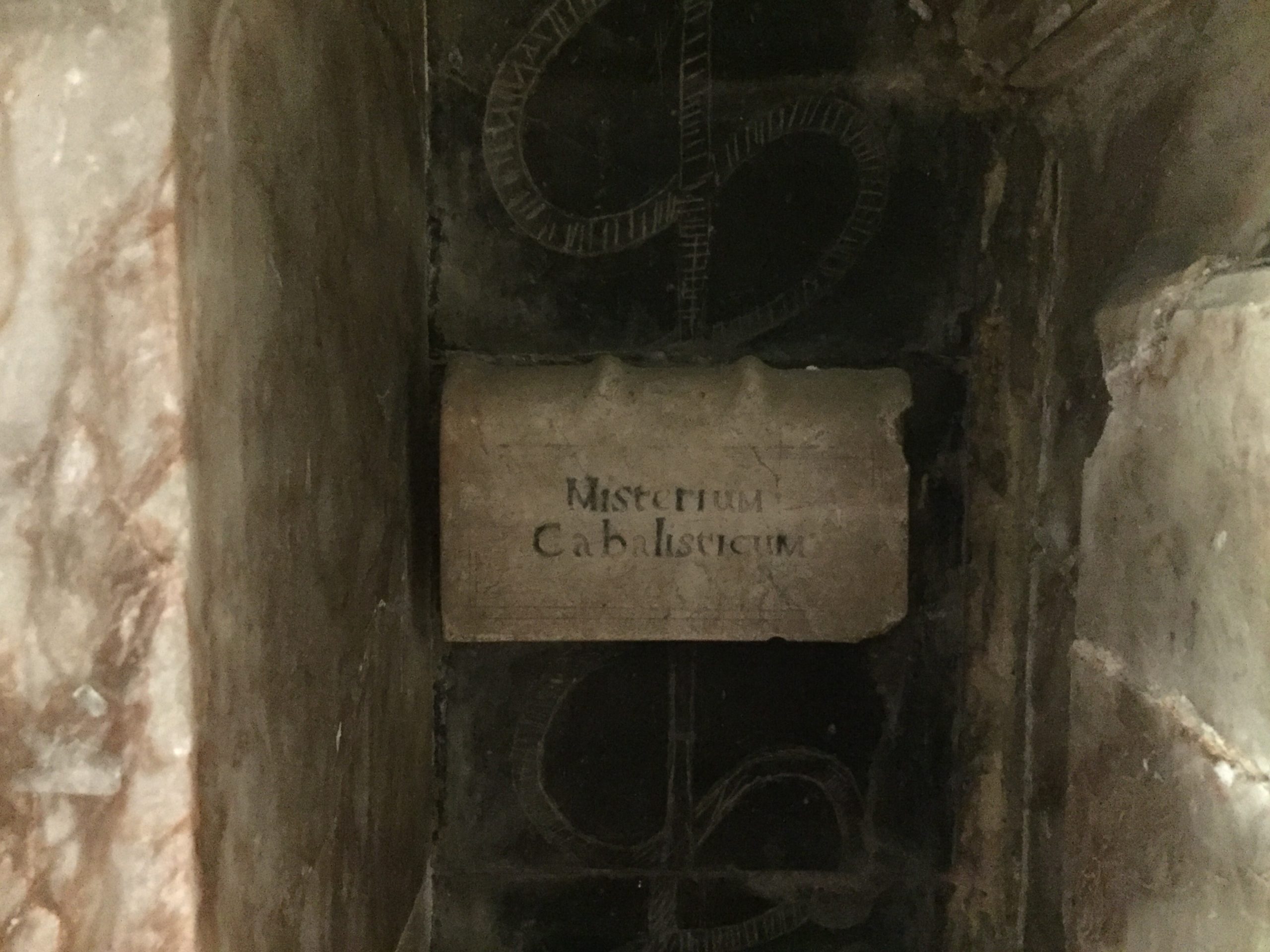

Jeremy Eichler reminds us that classical music is vital to our sense of continuity with the past, as well as preserving the inherited values of our collective identity. He argues that the music of memorial, written by the likes of Schönberg, Richard Strauss, Britten and Shostakovich, can reawaken shared memory far more effectively than even the most imposing physical monument, because music exists outside of time and speaks directly to the human heart. But, without our active engagement, these works will surely disappear and take their memories with them.

Eichler’s argument is convincing, not least because his prose possesses such fluency, precision and passion. The book is itself an act of memorialisation, even an act of cultural rescue. His research is meticulous, visiting locations associated with the composers and their works, delving also into their personal archives for original material to support his case. He discovers continued sensitivity around the reputations of these composers, as well as evidence of the personal and historical connections that existed between them. Read Eichler and suddenly classical music really matters again as a way of telling the human story with its search for universal truths in shared experiences. Can we then afford not to listen to this music, not to value it greatly, not to learn its timeless lessons?

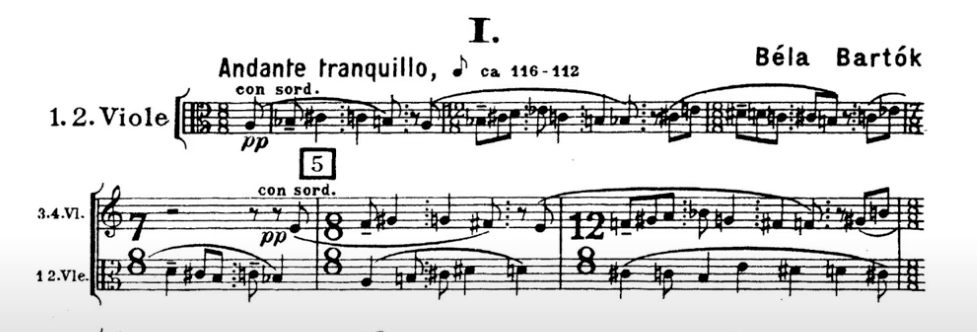

Eichler begins his account with the controversial figure of Arnold Schönberg, whose 7-minute narrated work from 1947, A Survivor from Warsaw, was a surprising hit after its first performance in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The music presents the listener with a visceral depiction of antisemitic violence and cruelty. Yet we soon discover that Serge Koussevitsky, who had commissioned the work through his Foundation, was queasy about performing it, despite himself being a Jew. Meanwhile, in post-war West Germany, the authorities felt obliged to alter the text to reduce its impact.

Schönberg always presented himself as an artist in ‘world historic’ terms, a vessel of progress and, according to Eichler, as the personal axis of a power struggle between German and Jewish culture. The burdens of history were always tearing him to pieces. In his youth, Schönberg had been an ardent Pan-German nationalist, devotedly following Wagner and writing ambitious works in a ripe late-Romantic style. He even invented serialism to secure ‘the supremacy of German Music,’ words that would later haunt him after he embraced his Jewish identity in response to the antisemitic persecution which forced him into exile in the USA.

His unfinished opera Moses und Aron (1932) sought a synthesis that could provide an answer to his crisis of identity. Moses represents the transcendent Word of God, which is incomprehensible to ordinary people for whom the divine message must be sugar-coated with lyrical sensuality. Moses lacks the knack for communication which Aron possesses, a shortcoming which acts upon him like a curse. The opera was never completed, in part because the work’s tension between intellect and feeling could not be resolved. To Schönberg, Judaism meant revering God as law, an abstract authoritarian presence, while German Romanticism increasingly represented to him a pagan world of love and longing. Although he claimed otherwise, the two sides of Schönberg’s character, heart and brain, were forever at war.

But did they have to be? Schönberg wanted to solve every problem with a once and for all solution, whether he was redrafting the timetable of the Berlin tram system or proposing the creation of a Unity Party to champion the cause of a Jewish homeland. His rigour took things to extremes. Eichler tells us that Schönberg sent his plan for a solution to the Jewish question to Thomas Mann for comment and received a lukewarm response. Mann warned him that his views might be perceived as ‘fascist’ in tone, even copying the antics of the Nazis. Schönberg had informed Mann that he himself intended to take charge of the party and would demand total obedience from its members. In truth, serialism was another product of his cerebral approach to communication, a way of exerting the intellect’s control over musical pitches. He had become Moses without Aron. Yet Eichler presents us with a sympathetic portrait of the defiant composer whose experiments with tonality had such a profound impact on music in the twentieth century.

Schönberg’s nemesis, we might imagine, would be the Bavarian composer, Richard Strauss, a thoroughly bourgeois character steeped in Wagner, who at first had supported the young Schönberg but came to consider him a madman. Strauss’s reputation has long been stained by his flirtations with the Nazi regime in the 1930s and for his egocentric Nietzschean outlook, which rejected religion and metaphysics in favour of ‘superman’ individualism. Some commentators perceive a direct link between Nazi ideology and Nietzsche’s revolutionary anti-Christian polemic.

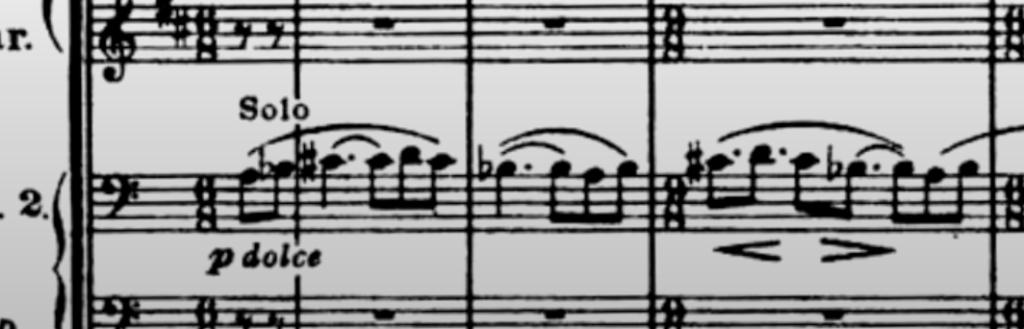

But Strauss, like Nietzsche, could never quite rid himself of a longing for transcendence which was the hallmark of German Romanticism. Yes, Strauss was naïve, often shallow and smug, but he was not a monster, and he came to regret his contact with senior members of the Nazi party. Eichler focuses on Strauss’s late masterpiece Metamorphosen (1945), a virtuosic work written for twenty-three solo strings. With a series of powerful insights, Eichler encapsulates Strauss’s grief and need for contrition. In particular, he draws our attention to the quotation from the funeral march of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony which Strauss tags In Memoriam towards the end of the score. Inevitably the question is asked, in memory of what? Eichler senses a deliberate ambiguity. Surely Strauss is not memorialising the fallen tyrant Adolf Hitler. Unlikely, since by this time, the regime had murdered his son’s mother-in-law and stripped Strauss of his official titles. But the beautiful and heroic dream of German Romanticism was certainly over, its cultural landmarks reduced to rubble. In Metamorphosen, Strauss remembers and regrets; remembers the idealism and visionary works of Beethoven, Wagner, Goethe et al, and regrets his own political naivety and capacity for superficial diversion. His music signals a painful confession. Eichler’s account of the work and Strauss’s state of mind is deeply moving, so that we can only feel sorrow and forgiveness towards the ageing composer.

Eichler then turns to a later work, Benajmin Britten’s pacifist statement, the War Requiem of 1962. He cites and questions the often-quoted myth that Britten was the first British composer of any significance since Henry Purcell, but he does not provide the evidence fully to dismiss the idea. What of the generation of Elgar, Holst and Vaughan Williams? The latter’s Third Symphony is surely one of the most poignant of all elegies for the fallen of the First World War, while his Sixth is an appropriately bleak response to the Second. Elgar also gave poignant voice to collective grief in The Spirit of England (1917), a work which Britten greatly admired.

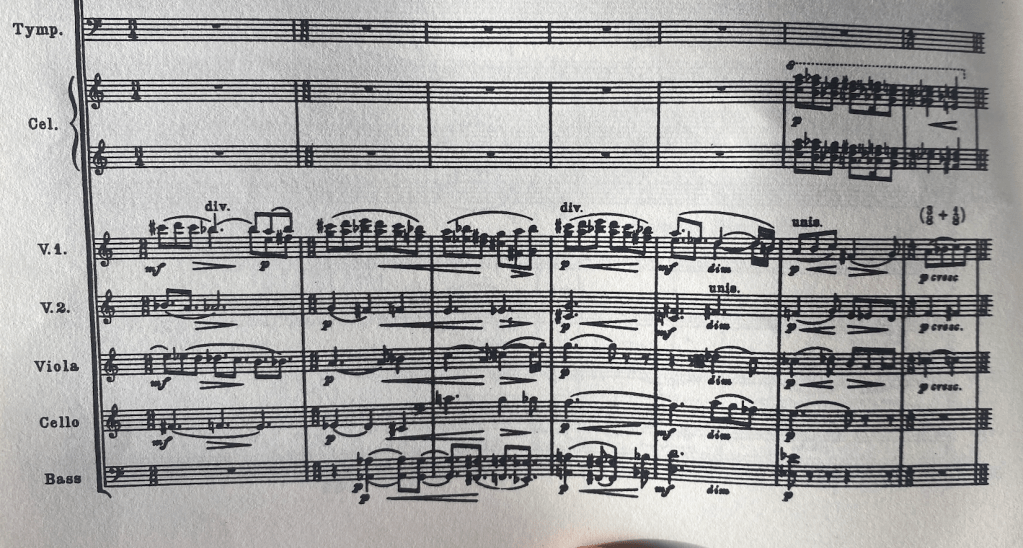

That said, Britten’s War Requiem uniquely attempts to bind modernity to the past, much like the new Coventry Cathedral for whose opening in May 1962 the piece was commissioned. The shell of a medieval church, bombed on a dark night in 1940, is juxtaposed with a concrete hangar of radical newness. The anima loci is not lost on Eichler, who describes both the new cathedral and Britten’s music as ‘a constant reminder of the thinness of civilisation’s veneer and of the human capacity for self-destruction.’ The War Requiem places the vivid religious theatre of grand Masses by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Berlioz and Verdi, alongside the subjective alienation of Wilfred Owen’s poetry from the First World War. It is a work of heartfelt grief, offering both a critical assessment of war and emotional consolation for the dead and those they leave behind. The first performance was as a public occasion the last time a living British composer of classical music could claim to act as a voice for the whole nation. But the work was also an act of international reconciliation, and its reach was also fascinating. According to Eichler, Shostakovich loved the work, risking the wrath of his political masters who had refused permission for a Russian soloist to be present at the premiere to sing the soprano part.

The friendship between the two composers led Shostakovich to dedicate his 14th symphony to Britten, a work that dances with death and flirts with nihilism, as disturbing as it is finely wrought. This despair had followed the controversy of Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony ‘Baba Yar’, a setting of poetry by Yevgeny Yevtushenko which commemorated the 30,000 victims, mainly Jewish, of a notorious massacre in the outskirts of Kiev in 1941. Eichler tells us that the Soviet leader Khruschev lectured Shostakovich face to face, complaining that such negative emotions undermined the optimism of the State and its citizens in their pursuit of a socialist Utopia.

Despite further intimidation of the performers by the regime, the premiere of the 13th Symphony went ahead, and audiences adored it. It touched a deep vein of unexpressed grief in the Russian soul. Shostakovich found himself under constant pressure to toe the official Soviet line, and it broke him physically and mentally. He was, like Thomas Mann’s protagonist in his novella Death in Venice, an artist torn between his need to be accepted by the Establishment and the personal torments that raged within. Such psychological conflicts are among the key messages of Eichler’s book. Artists of this stature are inevitably caught between the desire for the public accolades which flatter them and secure their livelihoods, and the call of their integrity that rebels against the fickle and shallow world of the governing classes; an elite eager to claim great art as an adornment to their vanity. Nobody endured political hypocrisy more than Shostakovich, and Eichler reminds us that, when he died, those who had condemned him most were first in the queue to accompany his coffin.

But Time’s Echo is primarily a book about how human societies grieve and remember grief, and the role that serious classical music plays in ensuring that we retain a relationship with the past and the dead upon whose shoulders we stand. For the Soviets, the horrific scale of sacrifice was not the issue. Their chief concern was to defend their country and political system, and the World Wars were, in their eyes, the product of bourgeois greed and exploitation. In Marxian terms, the wheels of destiny must be allowed to grind without human sentiment. Russian War memorials commemorated great loss of life, which was accepted as a necessary sacrifice in a process of national rebirth. Atrocities committed by Nazis against other racial groups within Russia, while not condoned, were not considered relevant to the Socialist project.

In Britain, a fetish for modernity was another attempt to forget. Britain was tired of struggle and saw the two World Wars as one protracted conflict against the fascist inclinations of mainland Europe. Eichler suggests with gentle admonition that the British were not that interested in the Holocaust in the immediate post-war period, applying censorship to sanitise the earliest film and journalistic reports. Benjamin Britten missed something significant, he claims, by not acknowledging the Jewish sacrifice in his War Requiem. But there is danger in setting one horrific war crime against another in some kind of grisly competition. If Russian indifference was ideological, then British reticence was to ensure their own national remembrance was not obscured by the overwhelming scale of Nazi violence. Eichler identifies that the crux of the War Requiem occurs with Britten’s setting of Owen’s poem ‘Strange Meeting,’ when a soldier meets the man he has killed in hell. A single human tragedy is thus elevated by music to the status of a universal symbol, marking the deaths of all victims of war.

According to Eichler, Germany remains shy of memorialising its past, as if Strauss’s evasions were not unusual. Some truths may be too difficult to face, and it should be no surprise that Germans did not like being cast as sadistic villains in A Survivor from Warsaw. Then art inevitably softens the brutality of lived experience. There is no doubt that the ritualisation of grief, making it beautiful to sense and glorifying sacrifice can give credence to what Wilfred Owen called ‘The old Lie’ – that there is something innately glorious in giving one’s life for one’s country. Music can dilute the visceral nature of human suffering like no other artform, so that even Schönberg’s restless dissonances cannot replicate the full terror of a real time and place. Afterall, his narrative in A Survivor from Warsaw is fictional. When, in its final bars, the male chorus sings the Shema Yisrael, we feel uplifted by their faith and heroic defiance, gladly forgetting the sense of futility and cruelty endured by most Holocaust victims. An act of redemptive imagination here obscures reality by turning it into something like an epic war film. Think of Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, which both disturbs and entertains with its Hollywood slickness, accompanied by John Williams’ tuneful score. By comparison, Primo Levi’s If This is a Man, a biographical account of life in the concentration camps, verges on the unreadable because he spares us nothing.

Levi wants us to taste the sinew and the blood, to arouse our anger and despair, although this brutal realism risks demoralising the reader. Eichler prefers to cling to hope, and he is indeed right to say that the musical masterpieces covered in his book are restorative acts of remembrance, even if they dilute the incomprehensible tragedies from which they originate. Reality is in such instances so disgusting that it cannot be recreated in art nor permanently held in memory. All healing processes include a degree of forgetting; a constructive amnesia that makes the unbearable bearable. We remember so that we can move on. Jeremy Eichler’s Time’s Echo tells us why classical music must remain part of our collective culture. It confers dignity and purpose upon those who have suffered and paid with their lives, and it binds us to them in moments of precious beauty. Without such music, there would only be despair.

Time’s Echo by Jeremy Eichler is available from Faber.

Peter Davison is a concert programmer and cultural commentator who was formerly artistic consultant to Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall.

For updates on new Corymbus posts, sign up to the mailing list.

You must be logged in to post a comment.